Suffering, it has been said, is meant for our conversion. Wherever you encounter it, whether your own or that of others, suffering ought to help return our hearts and minds to God.

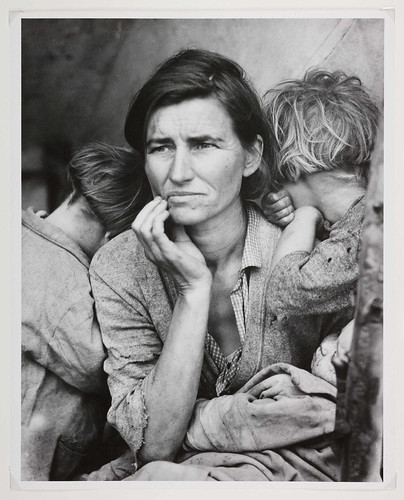

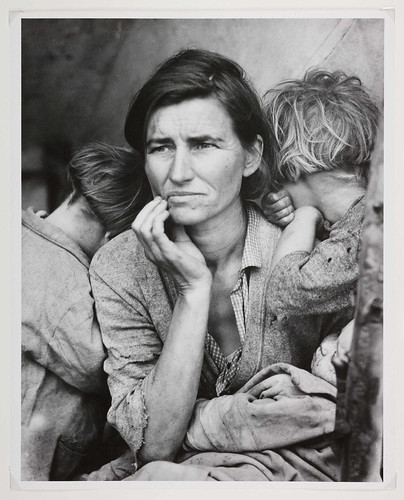

photo: D. Lange

Some pain is hidden; other hardships are obvious and in plain view. The man who can barely pedal his bicycle-rickshaw because it could never earn him enough to replace the calories he expends to do it--that man cannot conceal what a lifetime of material deprivation has meant to his body. The women who are eighteen but look to me like they are in their mid-thirties, and the ones who are hauling bricks long after they should be home and tucking their children into bed, can't hide it, either. Neither can the workers at the Fukushima plant or the people in the surrounding areas of tsunami-devasted Japan.

This kind of thing is what leads so many of us to (very ironically) classify sufferings based on severity or, worse, to dismiss one person's pain on the basis of our knowledge of a greater and more legitimate hardship "out there somewhere." How dare she complain about the broken dishwasher when there are millions who do not have running water in their homes! When you stop to think about it, this is a very clever diversionary tactic if it succeeds in preventing a person from considering the messy state of their own inner life. It is much easier to maintain the belief that it is "those others out there" who are really bad off.

With our attention focused on another, we are much less less likely to notice how the sufferings of others mirror our own. "Who me? No, I'm fine, I am not the one with real problems..."

With our attention focused on another, we are much less less likely to notice how the sufferings of others mirror our own. "Who me? No, I'm fine, I am not the one with real problems..."

My daughter's Catechism book gives two reasons for the Passion and the Crucifixion. Jesus suffered and died, it says, so that we would know the depth of the Father's love for us and the evil of sin. The book is aimed at first graders, so the language is straightforward. The authors, understandably, chose to dodge the theological arguments (and violence) that have raged over the past couple millenia about why Jesus had to die and how exactly one is saved. The book leaves the conversation about the mechanics of the salvific process alone and, rather, it says very simply that there are two things to contemplate when considering the sufferings and ultimate death that Jesus endured: love, and just how bad sin is.

Christianity teaches that all life reveals God, but most especially human life because God became a human person. The Church tells us that all of human experience is a manifestation of the Life that was lived by God-on-earth, but most especially the experience of suffering. Because Jesus suffered for our sake. More accurately, His sufferings are our sufferings.

In other words, the suffering Jesus, the One whose body is tired from trying to stay alive though overworked and underfed, is at once a metaphor and the reality of sin in the world. Out of the Father's great love, the Son took on all of the sin of the world, and it killed him. Suffering, then, is sin made visible.

In other words, the suffering Jesus, the One whose body is tired from trying to stay alive though overworked and underfed, is at once a metaphor and the reality of sin in the world. Out of the Father's great love, the Son took on all of the sin of the world, and it killed him. Suffering, then, is sin made visible.

Carryll H. and I have been spending lots of time together here in India. The first book of hers that I discovered was not one of her well-known works but actually an out-of-print collection of letters to close friends or acquaintances. There are echoes of her published pieces in the letters; it seems she was never tired of repeating what the saints have always said: Christ lives in the littlest and lowliest. This is where He usually chooses to manifest Himself. She must have feeling a bit catty one day because in one letter she was almost ridiculing the folks who celebrated St. Therese's canonization. It shouldn't be so surprising that someone like this little French girl could become a saint and live with God in heaven, said Carryll. The more surprising thing is that Jesus would actually live in someone like Therese, quintessential bourgeoise that she was!

from D. Lange's "Migrant Mothers" Depression-era series

Every person, said Mother Teresa, has been created for great things: to love and to be loved. Rich and poor alike. And yet both Mother and Carryll agreed that those who are poorest and sickest and suffering most acutely have the most to teach the world about love. We need them and we owe the poor a great debt, Mother said, because they show us how much we need God.

Suffering, wherever we encounter it, is for our conversion. It is not useless; it can make us holy. The marks on those who suffer show us the wounds of our not-always-visible sin. We may try to conceal them, but the obvious neediness of the poor, the sick and the neglected aren't going to let us get away with it.

To you, O Lord, I make my prayer for mercy. Heal my soul, for I have sinned against you. - from Evening Prayer, Lenten Season